Lattès maps and Weierstrass elliptic functions

Published:

For any rational map $f(z)$ on the Riemann sphere $\mathbb{P}^1$ onto itself, can its Julia set $J(f)$ be the whole Riemann sphere? When it is the case, the Fatou set $F(f)$ is empty and it tells us that $f$ is chaotic throughout the whole $\mathbb{P}^1$. The answer is yes. In this post, I will discuss one standard way of constructing such rational maps, often called Lattès maps.

Recall from my previous post that the Julia set $J(g)$ of any holomorphic self map $g(z) = \alpha z$ of a complex torus $\mathbb{T} = \mathbb{C} / \Lambda$ which fixes the lattice $\Lambda$ is the whole torus $\mathbb{T}$ whenever $\vert \alpha \vert > 1$. The idea is to use such a map $g$ and transfer it from the torus $\mathbb{T}$ to the Riemann sphere $\mathbb{P}^1$. How do we exactly perform this transfer?

Construction of Lattès maps

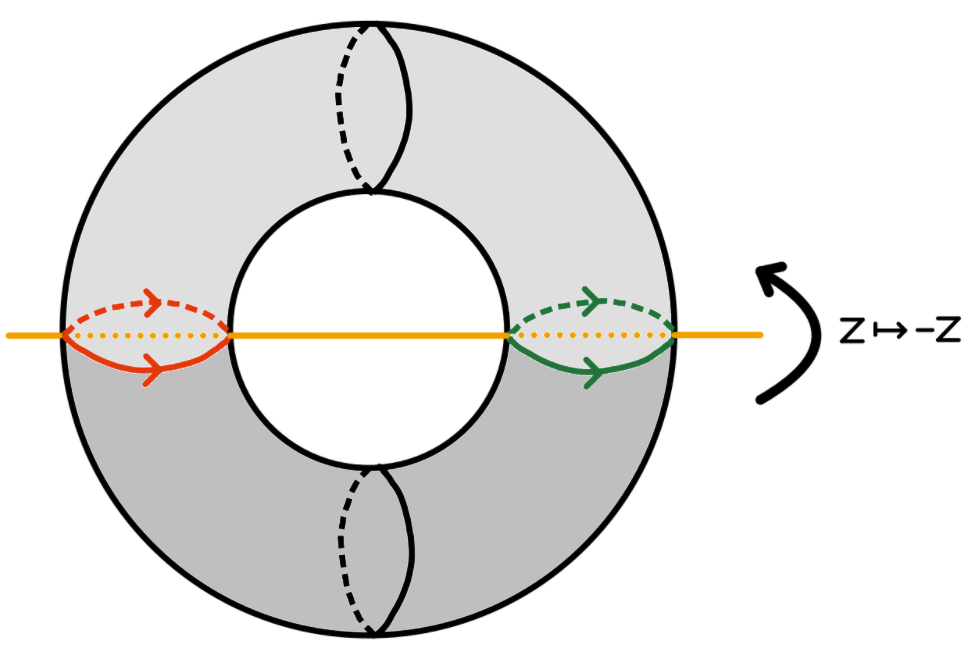

The map $z \mapsto -z$ is a well-defined involution from $\mathbb{T}$ onto itself. Topologically, this action appears to flip the donut. (See the diagram below!) The fundamental domain of this action is half the donut and by gluing the corresponding edges, we obtain a topological sphere. As the sphere admits a unique complex structure, the quotient of $\mathbb{T}$ under this involution is the Riemann sphere $\mathbb{P}^1$.

What remains is to construct a rational map $f$ from $g$. Let $\pi : \mathbb{T} \to \mathbb{P}^1$ be the holomorphic quotient map induced by the involution. Since $g$ is a linear map, it commutes with $z \mapsto -z$ and the map $g$ descends to a unique rational map $f$ such that $f\circ \pi = \pi \circ g$. (In dynamical systems, $\pi$ is called a semi-conjugacy between $f$ and $g$.) Now, the action of $f$ on $\mathbb{P}^1$ very much resembles the dynamics of $g$ on $\mathbb{T}$. In particular, as repelling periodic points of $g$ are dense in $\mathbb{T}$, then so are the repelling periodic points of $f$ in $\mathbb{P}^1$. Therefore, $J(f) = \mathbb{P}^1$.

A rational map $f$ obtained from such a construction above is called a Lattès map. Some explicit examples of Lattès maps can be easily computed. In Milnor’s book3 $\S 7$, he showed by elementary computation that the rational map $f(z) = \frac{i}{2}(z + \frac{1}{z})$ is a degree $2$ Lattès maps. He did this using the simplest lattice $\Lambda$ possible, which is the set of Gaussian integers $\mathbb{Z}[i]$, and the linear map $g(z)=(1+i)z$. I do have to point out that there are other examples of non-Lattès rational maps $f$ with $J(f)=\mathbb{P}^1$; these were found by Mary Rees4 and all of their critical points are eventually mapped to a repelling periodic orbit.

Weierstrass $\wp$-function

As an analyst, one may be rather unsatisfied by the way I construct $\pi$ above. We can fix this as follows. First, observe from our construction of $\pi$ that $\pi$ must be an even function. Let $a$ and $b$ be the periods of $\Lambda$, i.e. complex numbers generating the lattice $\Lambda$. As the involution fixes $0$, $\frac{w_1}{2}$, $\frac{w_2}{2}$ and ${w_1+w_2}{2}$ (mod $\Lambda$), $\pi$ is a double covering map branched at these four points. Let’s assume that the branch point $0$ is a pole, i.e. $\pi(0)=\infty$, and that the Laurent series about $0$ is of the form

\[\pi(z) = \frac{1}{z^2} + \sum_{n>0 \text{ even}} a_n z^n.\]\[\wp(z) = \frac{1}{z^2} + \sum_{w \in \Lambda \backslash \{0\}} \left( \frac{1}{(z-w)^2} - \frac{1}{w^2} \right).\]Proposition: The map $\pi$ coincides with the Weierstrass’s $\wp$-function $\wp : \mathbb{T} \to \mathbb{P}^1$,

Let’s prove the proposition. First, for any $z \in \mathbb{C}$ and any lattice point $w \in \Lambda$ such that $\vert w \vert > 2 \vert z \vert$, we have the inequality $\vert w \vert \leq 2 \vert z-w \vert$ and therefore

\[\Big\vert \frac{1}{(z+w)^2} - \frac{1}{w^2} \Big\vert = \Big\vert \frac{z(2w-z)}{w^2(z-w)^2} \Big\vert \leq 6 \Big\vert \frac{z}{w^2} \Big\vert.\]Convergence of $\wp(z)$ then follows from the inequality above and the fact that the sum $\sum_{w \in \Lambda \backslash {0}} \frac{1}{\vert w \vert^3}$ converges.

Let $w_1$ and $w_2$ be the periods of $\Lambda$. Clearly, the derivative $\wp’(z) = - 2 \sum_{w \in \Lambda} (z-w)^{-3}$ satisfies $\wp’(z+w_j) - \wp’(z) = 0$ for any $z$ and any $j \in {1,2}$. Then, for each $j$, $\wp(z+w_j)-\wp(z)$ is a constant map of some constant value $c_j$. Taking $z = -\frac{w_i}{2}$, we see that $c_j = 0$ and $\wp$ must be $w_j$-periodic for each $j$. Therefore, $\wp$ is a well-defined map on $\mathbb{T} = \mathbb{C} / \Lambda$. Both $\wp$ and $\pi$ have the same principal parts on $\Lambda$. The difference $\wp - \pi$ must be constantly zero, thus proving that $\pi \equiv \wp$.

The study of Weierstrass elliptic functions is interesting in its own right. I’d happily recommend looking at more details from Ahlfors’ book1.

References

1: L. Ahlfors. Complex Analysis. McGraw-Hill, 1979.

2: A. Beardon. Iteration of Rational Functions. Grad. Texts Math. 132, Springer-Verlag, NY, 1984.

3: J. Milnor. Dynamics in one complex variable. Princeton University Press, third edition, 2006.

4: M. Rees, Positive measure sets of ergodic rational maps, Ann. Sci. Ecole Norm. Sup. 19 383–407. 1984.