Summary of my PhD thesis

Published:

The summer went by so quickly, and I still can’t believe I am finally done with grad school! Somehow I managed to write a 230 page long PhD thesis. Am I going insane? Well, that’s not the question I would like to answer just yet. If whoever is reading this is interested in my research and is intimidated by the page count, you are in the right place! Below, I will try to summarize my PhD thesis omitting most of the technical details.

A little background

My research is on complex dynamics, aka the study of iterations of holomorphic maps. The primary object I dealt with in my thesis is the following. Given a holomorphic map $f: U \to \mathbb{C}$ on a planar domain $U \subset \mathbb{C}$, let’s call a Jordan curve $X \subset \mathbb{C}$ a Herman curve of $f$ if

- it is invariant under $f$ (i.e. $f(X)=X$),

- $f:X \to X$ is topologically conjugate to an irrational rotation $R_{\theta}(z) = e^{2\pi i \theta} z$ on the unit circle $S^1 = \{\lvert z \rvert = 1\}$,

- $X$ is not contained in a rotation domain, i.e. an invariant open disk or annulus $D$ on which $f_D$ is conjugate to $R_\theta$ on either the unit disk $\{\lvert z \rvert < 1\}$ or some round annulus $\{1<\lvert z \rvert < r\}$. The irrational number $\theta \in (0,1)$ is called the rotation number of $(f,X)$.

Rotation domains are quite well studied, and their existence has long been known. In general, it is much more challenging to produce examples of and study the properties of invariant curves compared to invariant domains. For example, the interest in invariant curves goes back to more than 100 years ago by the works of Fatou.

The simplest kind of example of Herman curves is the unit circle. Here are a few elementary examples:

- Arnol’d map: For any irrational $\theta$, there is a unique $\alpha=\alpha(\theta) \in (0,1)$ such that the circle $\mathbb{R} / \mathbb{Z}$ is a Herman curve with rotation number $\theta$ of the map $f(z) = z + \alpha + \frac{1}{2\pi}\sin(2\pi z)$ acting on the cylinder $\mathbb{C}/\mathbb{Z}$.

- Blaschke product: For any irrational $\theta$, there is a unique $\alpha=\alpha(\theta) \in (0,1)$ such that the unit circle $S^1$ is a Herman curve with rotation number $\theta$ of the map $f(z) = e^{2\pi i \alpha} z^2 \frac{z-3}{1-3z}$ acting on the Riemann sphere $\hat{\mathbb{C}} = \mathbb{C} \cup \{\infty\}$.

A question one can ask is the following: does there exist an example of a global holomorphic map $f$ (global = acting on the whole of $\hat{\mathbb{C}}$ or $\mathbb{C}$ or $\mathbb{C}/\mathbb{Z}$) admitting a Herman curve $X$ that is not a round circle?

In general, by deforming complex structures, a round circle example $(f_0,X_0)$ can be modified to another Herman curve $(f_1,X_1)$ that is no longer a round circle, but this procedure still gives a conjugacy between $f_0$ and $f_1$ on a neighborhood of $X_0$, so in some sense the right question to ask ourselves would be whether or not there exists a Herman curve that are not “equivalent” to a round one.

I gave a satisfactory answer to this question under the assumption that the rotation number $\theta$ is of bounded type, that is, $\theta$ has continued fraction expansion $[0;a_1,a_2,a_3,\ldots]$ where $\sup_n a_n < \infty$. The bounded type assumption essentially states that $\theta$ cannot be well approximated by any rational number at all scales. (See this old post.) Many things I’m going to say below may not always hold for unbounded type…

Herman1 and Yoccoz2 proved that if an irrational $\theta$ satisfies some complicated arithmetic assumption (that holds true for bounded type ones), then every analytic diffeomorphism $g:S^1 \to S^1$ of the unit circle with rotation number $\theta$ always admits an analytic conjugacy $h:S^1 \to S^1$ such that $h\circ g \circ h^{-1} = R_\theta$. As a consequence of the Herman-Yoccoz result, every Herman curve $(f,X)$ with bounded type rotation number admits at least one inner critical point and at least one outer critical point on $X$. A point $c \in X$ is an inner critical point if there’s some $d_0 \geq 2$ such that for every point $w$ close to $f(c)$ located inside of $X$, there are $d_0$ points in $f^{-1}(f(w))$ near $c$ located inside of $X$. Similarly, we call $c \in X$ an outer critical point if there’s some $d_\infty \geq 2$ such that for every point $w$ close to $f(c)$ located outside of $X$, there are $d_\infty$ points in $f^{-1}(f(w))$ near $c$ located outside of $X$.

For simplicity, every Herman curved mentioned below will be assumed to be of bounded type and to be unicritical, i.e. has one critical point $c$; hence, $c$ is both an inner and an outer critical point. We will call the numbers $(d_0,d_\infty)$ the criticality of the Herman curve.

The short pitch

The question I formulated above is answered by the following theorem if we pick $d_0 \neq d_\infty$.

Realization Theorem: For any integers $d_0, d_\infty \geq 2$ and any bounded type irrational $\theta$, there exists a rational map $f:\hat{\mathbb{C}} \to \hat{\mathbb{C}}$ which admits a unicritical Herman curve $X$ with rotation number $\theta$ and criticality $(d_0,d_\infty)$.

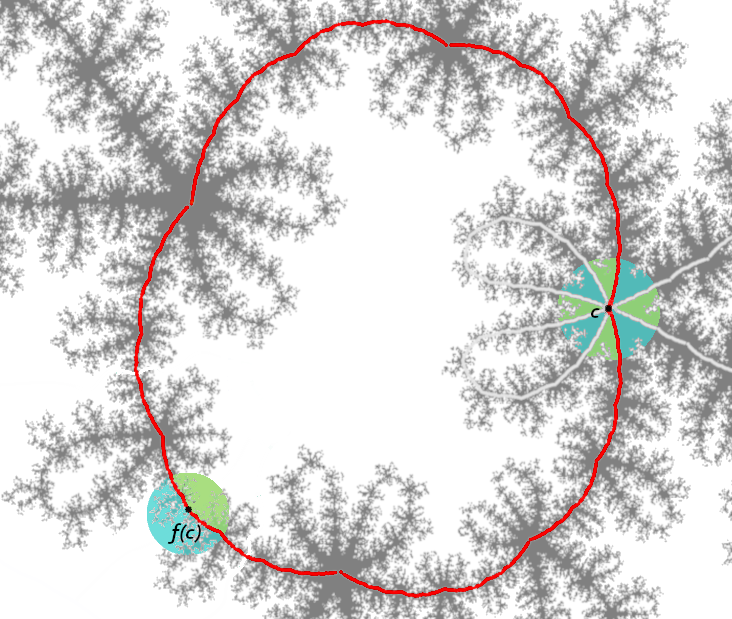

In the proof of the theorem, the example $(f,X)$ is constructed very carefully by studying bounds on annular rotation domains (Herman rings) and studying degenerations of such objects. An example of the Herman curve with data $\theta=\frac{\sqrt{5}-1}{2}$ and $(d_0,d_\infty)=(3,2)$ is shown below.

The proof works in the presence of multiple inner and outer critical points placed anywhere you like, but for brevity we will just discuss the simplest case. Also, the Herman curve $X$ that I constructed actually has the regularity of a quasicircle! (See this other old post about quasicircles.) Currently, no one really knows if there exist an example of a Herman curves that is not a quasicircle. In what follows, we will just assume that any Herman curve discussed has the regularity of a quasicircle.

Rigidity Theorem: Given two Herman curves $(f, X)$ and $(g,Y)$ of the same bounded type rotation number $\theta$ and criticality $(d_0,d_\infty)$, there exists a quasiconformal conjugacy $\phi$ between $f$ and $g$ on the neighborhoods of $X$ and $Y$. Moreover, $\phi$ is $C^{1+\alpha}$ along $X$.

Here, $C^{1+\alpha}$ means that the complex derivative $\phi’(z)$ exists for all $z \in X$, and $\phi’$ is uniformly H"older continuous on $X$. This theorem has many many many unexpected consequences! Here are a few of them:

- The Hausdorff dimension of $X$ is equal to that of $Y$.

- $X$ is a $C^1$ smooth Jordan curve if and only if $X$ has Hausdorff dimension $= 1$ if and only if $d_0=d_\infty$.

- If $\theta$ is a quadratic irrational (i.e. it has preperiodic continued fraction, see here), then $X$ is asymptotically self-similar at the critical point with universal scaling constant depending only on $\theta$ and $(d_0,d_\infty)$.

The Rigidity Theorem is a consequence of studying renormalizations of Herman curves. Renormalization essentially means that you restrict yourself to a subdomain $I$ (in this case a subinterval of $X$) and consider the first return map $F(z)$ to this subdomain, i.e. $F(z) = f^k(z)$ where $k$ is the smallest positive number such that $f^k(z)$ is contained in $I$ again. Renormalization theory is nowadays a very powerful principle in complex dynamics and it provides a way to explain many deep phenomena. For example, the MLC conjecture, which states that the Mandelbrot set is locally connected, is now reduced to a conjecture on renormalizations of quadratic maps.

Here’s another deep result that one can get out of studying the renormalization operator:

Regularity Theorem Consider a Herman curve $(f,X)$ with a quadratic irrational rotation number $\theta$ and some criticality $(d_0,d_\infty)$. Pick a skinny annular neighborhood $A$ of $X$ and consider the Banach ball $\mathbf{B}$ consisting of holomorphic maps $g: A \to \mathbb{C}$ admitting a single critical point and satisfying $\sup_{z\in A}|f(z)-g(z)|<\delta$ for some small constant $\delta>0$.

- The space $\mathbf{S}$ of maps $g \in \mathbf{B}$ which admit a Herman curve $X_g$ with the same rotation number $\theta$ and criticality $(d_0,d_\infty)$ forms an analytic submanifold of $\mathbf{B}$ of codimension at most one.

- The quasicircle $X_g$ moves continuously and holomorphically in $g \in \mathbf{S}$.

Of course, conjecturally, this theorem should be true for all bounded type rotation number. I also believe the codimension should really be equal to one, but this seems like a very difficult problem. Hopefully, I can address this in the future, or maybe whoever reading this blog post can work with me and maximize our joint slay. :)

References

1: Michael Herman. Sur la conjugaison différentiable des difféomorphismes du cercle à des rotations. Publ. Math. IHÉS, 49:5–233, 1979.

2: Jean-Christophe Yoccoz. Analytic linearization of circle diffeomorphisms. In Dynamical Systems and Small Divisors, vol. 1784 of Lecture Notes in Math., pages 125–173. Springer, 2002.