Classification of 2-D orbifolds

Published:

Now that we know orbifolds (see this post), we would like to make an attempt to classify the geometries of all 2 dimensional connected orbifolds. I would like to start off with the theory of covering spaces of orbifolds and then make a classification statement according to the universal cover of these spaces, similar to the uniformisation theorem and the classical classification of surfaces.

Covering Space Theory

We say that a continuous map $f: O \to P$ between two orbifolds is an orbifold covering map if it is surjective and every $y \in P$ admits an evenly covered neighborhood $V$ such that

- The preimage $f^{-1}(V)$ is a disjoint union of connected open sets $U_1, U_2, \ldots$ in $O$,

- Each restriction $f: U_i \to V$, after passing to local charts, is a quotient map between two quotients of $\mathbb{R}^n$ by finite groups.

The definition above very much mirrors the usual definition of covering maps between topological spaces. What’s new is that at each singularity point (where the isotropy group is nontrivial), we allow $f$ to act as a quotient map instead of a local homeomorphism, that is, if $V=W/\Gamma$ for some finite group $\Gamma$ acting on an open subset $W \subset \mathbb{R}^n$, then $U_i$ is isomorphic to $W/\tilde{\Gamma}$ for some subgroup $\tilde{\Gamma}$. When $O$ and $P$ are smooth orbifolds, we say that $f$ is smooth if we additionally require that every restriction $f: U_i \to V$ lifts to a smooth map from $W$ to itself. We will from now on only consider smooth orbifolds and coverings for convenience.

An orbifold covering map $f: \tilde{O} \to O$ is a universal orbifold covering map if it satisfies the universal property similar to that in the usual sense. Its existence can be shown by inverse limits. (Refer to Thurston’s original paper2 for details.) The main idea is that $\tilde{O}$ must be the cover which has the least bad singularities (or equivalently, the strongest quotient maps on every local chart). We say that $O$ is good if its universal cover $\tilde{O}$ is a smooth manifold, bad if otherwise. It is rather unfortunate that bad orbifolds do actually exist… We will see why in a few minutes!

Euler Characteristic

Let’s assume that $O$ is a compact 2-D orbifold (possibly with topological boundary). Recall (from here) that every singularity of $O$ must be either a cone point, a corner reflector, or a mirror boundary. Endow $O$ with a finite CW complex structure such that every singular point and mirror boundary is a cell, so that each cell $c$ has a well-defined isotropy group $\Gamma(c)$. The orbifold Euler characteristic of $O$ is defined to be

\[\chi(O) = \sum_{\text{cell } c} \frac{(-1)^{\text{dim(c)}}}{\vert \Gamma(c) \vert}.\]The quantity $\chi(O)$ is independent of the choice of the CW complex. The definition above can be generalised to higher dimensional compact orbifolds with boundary. When $O$ has $p$ cone points of order $m_1, \ldots m_p$ and $q$ corner reflectors of order $n_1, \ldots n_q$, we can rewrite the Euler characteristic as

\[\chi(O) = \chi_{CW}(O) - \sum_{i=1}^p (1-\frac{1}{m_i}) - \frac{1}{2} \sum_{j=1}^q (1-\frac{1}{n_j}),\]where $\chi_{CW}(O)$ is the usual topological Euler characteristic. There are two main reasons why we define $\chi(O)$ to be as such. Firstly, when $O$ is a manifold, all isotropy groups $\Gamma(c)$ are trivial and $\chi(O)$ coincides with $\chi_{CW}(O)$. Secondly, we still have the following formula.

Riemann-Hurwitz Formula: If $f: O \to P$ is a degree $d$ covering map between two compact $2$-D orbifolds, $\chi(O) = d \chi(P)$.

The proof of the formula is rather straightforward. Pick any $y \in P$ and let $x_1,x_2, \ldots$ be the preimages of $y$. Let $V$ be an evenly covered neighborhood of $y$ and $U_i$ be the corresponding connected component of $f^{-1}(V)$ containing $x_i$. Then,

\[d = \sum_{i} \text{deg}(f\vert_{U_i}) = \sum_{i} \frac{\vert\Gamma_P(y)\vert}{\vert\Gamma_O(x_i)\vert} = \vert\Gamma_P(y)\vert \sum_{i} \frac{1}{\vert\Gamma_O(x_i)\vert}.\]We then sum the corresponding equation above over every cell on $P$ (given some reasonably fine CW complex on P) in order to get the Riemann-Hurwitz formula.

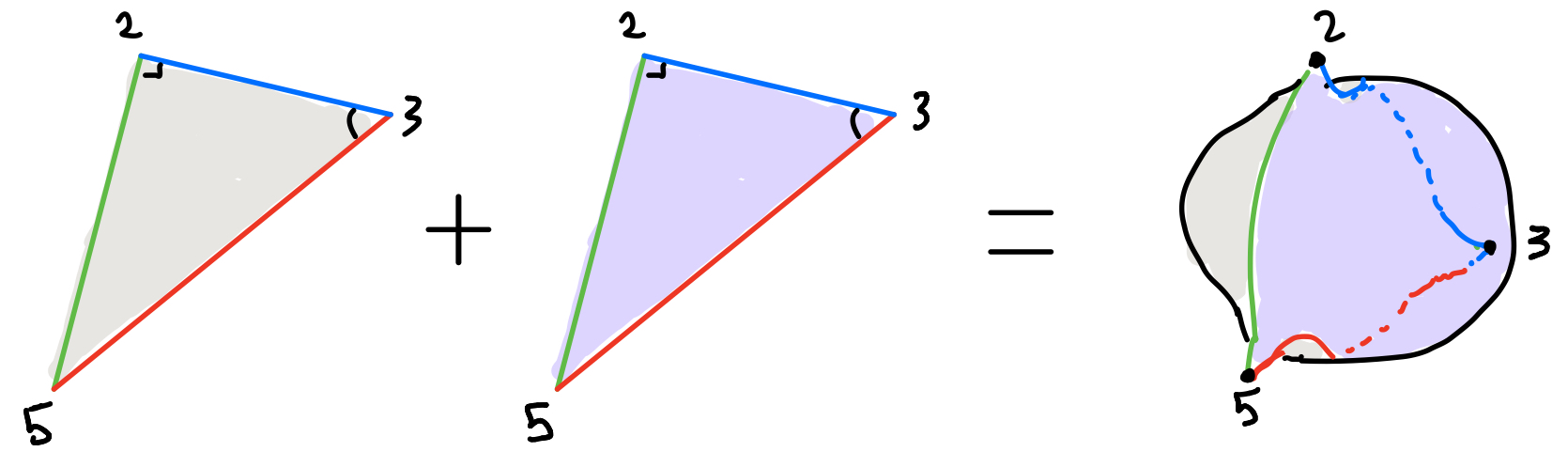

Let’s look at the following example. The triangle group $\Delta(2,3,5)$ is the group of icosahedral symmetries of the sphere $S^2$. This is the group of symmetries of the regular soccer ball. The orbifold $O = S^2 / \Delta(2,3,5)$ is essentially a spherical triangle with interior angles $\frac{\pi}{2}$, $\frac{\pi}{3}$, and $\frac{\pi}{5}$ at the vertices, which are corner reflectors of order $2$, $3$, and $5$ respectively. Obtain the double $P$ of $O$ by gluing two copies of $O$ along corresponding mirror boundaries. The orbifold $P$ is also isomorphic to $S^2 / \Gamma$ where $\Gamma$ is the subgroup of all orientation preserving symmetries in $\Delta(2,3,5)$. $P$ is a topological sphere with $3$ cone points of orders $2$, $3$, and $5$. The projection map $P \to O$ is an orbifold double covering map. We can easily verify that the Riemann-Hurwitz formula holds: $\chi(O) = \frac{1}{60}$ whereas $\chi(P) = \frac{1}{30}$.

Classification

Every compact surface is homeomorphic to either the sphere $S^2$, the 2-torus $\mathbb{T}^2$, the real projective plane $\mathbb{R}\mathbb{P}^2$ or the connected sum of multiple copies of $\mathbb{T}^2$ and/or $\mathbb{R}\mathbb{P}^2$. Any surface $S$ admits a geometric structure coming from its universal cover (elliptic if $\chi_{CW}<0$ and covered by $S^2$, parabolic if $\chi_{CW}=0$ and covered by $\mathbb{R}^2$ and hyperbolic if $\chi_{CW}<0$ and covered by $\mathbb{H}^2$). Similarly, we can endow any good compact 2-D orbifold $O$ with elliptic / parabolic / hyperbolic structure by endowing it with the Riemannian orbifold structure coming from its universal cover $\tilde{O} \in \{ S^2, \mathbb{R}^2, \mathbb{H}^2\}$.

To classify all 2-D compact Riemannian orbifolds, the following considerations must be made:

- By the classification of surfaces, if a 2-D compact orbifold $O$ is non-hyperbolic and has no boundary, $O$ must topologically be $S^2$, $\mathbb{T}^2$, $\mathbb{R}\mathbb{P}^2$, or the Klein bottle $K$; if $O$ non-hyperbolic with mirror boundary, then $O$ must be either a closed disk $D^2$, a closed annulus $A$, or a closed Mobius strip $M$.

- If $O$ has mirror boundaries, then we can instead consider the double $P$ obtained by gluing two copies of $O$ along all corresponding mirror boundaries. (If all are considered, $P$ is compact.) Any corner reflector in $O$ corresponds to a cone point in $P$ of the same order.

- More and worse singularities contribute to lower orbifold Euler characteristic. Therefore, the non-hyperbolic ones must not have too many singularities.

- If $O$ is elliptic, it is finitely covered by $S^2$ and Riemann-Hurwitz formula provide restrictions to the possible value of $\chi(O)$. If $O$ is parabolic, then the equation $\chi(O) = 0$ already gives a natural restriction.

Let’s encode the singularities of $O$ by a string of numbers called signature. If $O$ has $p$ cone points of order $m_1, \ldots m_p$ and no mirror boundary, then we define the signature of $O$ to be $(m_1, \ldots m_p)$. If $O$ has mirror boundary, we add the symbol $;$ after the $m_i$’s. If additionally $O$ has $q$ corner reflectors of order $n_1, \ldots n_q$, then the signature is $(m_1, \ldots m_p ; n_1, \ldots n_q) The four statements above would lead to the following table of all possible non-hyperbolic compact 2-D surfaces.

| Type | Topology | Signature |

|---|---|---|

| Bad | $S^2$ | $(m)$, $(m_1, m_2)$ [$m_1 < m_2$] |

| Bad | $D^2$ | $(;n)$, $(;n_1,n_2)$ [$n_1 < n_2$] |

| Elliptic | $S^2$ | $()$, $(m,m)$, $(2,2,m)$, $(2,3,k)$ [$3\leq k \leq 5$] |

| Elliptic | $D^2$ | $(;)$, $(n;)$, $(3;2)$, $(2;n)$, $(;n,n)$, $(;2,2,n)$, $(;2,3,k)$ [$3\leq k \leq 5$] |

| Elliptic | $\mathbb{R}\mathbb{P}^2$ | $(;)$, $(m;)$ |

| Parabolic | $S^2$ | $(3,3,3;)$, $(2,4,4;)$, $(2,3,6;)$, $(2,2,2,2;)$ |

| Parabolic | $D^2$ | $(4;2)$, $(3;3)$, $(2,2;)$, $(2;2,2)$, $(;3,3,3)$, $(;2,4,4)$, $(;2,3,6)$, $(;2,2,2,2)$ |

| Parabolic | $\mathbb{R}\mathbb{P}^2$ | $(2,2;)$ |

| Parabolic | $\mathbb{T}^2$ | $()$ |

| Parabolic | $K$ | $()$ |

| Parabolic | $A$ | $(;)$ |

| Parabolic | $M$ | $(;)$ |

All of the orbifolds above are in fact correct in the following sense:

- The good ones can in fact be covered by $S^2$ and $\mathbb{R}^2$. As an example, any of the parabolic orbifolds above with signature $(;a,b,c)$ are isomorphic to the quotient of the triangle group $\mathbb{R}^2/\Delta(a,b,c)$. In full generality, the seventeen parabolic compact orbifolds correspond to the seventeen wallpaper groups. (Refer to Conway’s magical book for pretty pictures and elementary explanations.)

- There are no bad compact 2-D orbifolds of negative Euler characteristic. This perhaps require a deeper study of hyperbolic orbifolds. Thurston showed this by a technique similar to the decomposition of pants.

References

1: J. H. Conway, H. Burgiel, C. Goodman-Strass, The Symmetries of Things. A K Peters, 2008.

2: W. Thurston, Three-dimensional geometry and topology. Vol. 1. Edited by Silvio Levy. Princeton Mathematical Series, 35. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1997.